The year: 1959

The place: Anaheim, CA

image source: Disney Universes

After a trip to the Swiss Alps — and a movie inspired by it — Walt Disney opened the Matterhorn Bobsleds in Disneyland. It was the park’s first roller coaster, and the world’s first coaster built with the now-standard tubular steel tracks. In 1975, Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom would get its own version of the Matterhorn in the form of Space Mountain, followed by a smaller, less whiplash-inducing version in Disneyland two years later. Then, in 1979 and 1980, Big Thunder Mountain was opened in Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom, respectively.

That was pretty much it for roller coasters for a while. EPCOT Center would open in 1982 with no thrill rides whatsoever — just a bunch of shows, Omnimover dark rides, and a couple of flume rides with no drops. Tokyo Disneyland opened in ’83 with just the two mountains (Space and Big Thunder, duplicates of Disneyland’s), and the Disney-MGM Studios opened in ’89 with… well, pretty much just one moving theater dark ride and a tram tour.

Then came Disneyland Paris…

Or Euro Disneyland, as it was then known.

EuroDisney was struggling, to put it kindly. To be more precise, it was drowning. Losses on the resort in France were so great, it was jeopardizing the company as a whole, causing major budget cuts to the other resorts, and shameless cash-grabs for the studio (mostly in the form of direct-to-video cheapquels). They needed to do something, fast, or risk losing it all.

Their Hail Mary was a roller coaster. Two, in fact. The park opened with a recreation of Big Thunder Mountain, to which they added a year later an off-the-shelf track layout from an outside contractor, Intamin, (very) loosely themed to Indiana Jones (essentially replacing a much more elaborate — and expensive — Indy ride on the planning board). The addition of another tangible thrill ride, including Disney’s first inversion, boosted attendance slightly; but more importantly, kept the park on life support until the real big gun was pulled out…

…literally.

image source: Theme Park Tourist

Less than two months after the failing park’s third anniversary, Disney opened Space Mountain: De la Terre à la Lune, a Jules Verne-inspired reimagining of the Disney parks classic that included two Disney firsts — an accelerated launch themed as a giant, rocket-firing cannon, and multiple inversions. Costing nearly $90 million in 1995, Space Mountain in Paris’ Discoveryland practically saved the resort and continues to thrill guests to this day, following two rethemes, one in 2005, and another, Star Wars-themed one in 2017.

Crossing back over the Atlantic, returning home to Walt Disney World, the Disney-MGM Studios was similarly struggling. While Epcot was getting almost a complete overhaul, the Studios was stagnating. Sure, The Twilight Zone Tower of Terror was enough to bring people into the park, but once there, it still wasn’t much more than a half-day park — even less if you were bored with taking the same Backlot and Animation Studio Tours you may have already seen before and watching random strangers perform on-stage in front of blue screens and foley props.

The recent Sunset Boulevard expansion had opened up a lot of additional space beside and behind the animation building, so for the park’s 10th anniversary, Disney decided to try to capture lightning in a bottle again (instead of an elevator shaft, I suppose), by building another coaster here in the U.S. The Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster Starring Aerosmith wouldn’t be an exact duplicate of Paris’ Space Mountain, but it would feature an accelerated launch, two loops, and a corkscrew, just like its European cousin.

Despite being egregiously out of place in what was supposed to represent 1940s Hollywood, the Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster was a huge hit with guests, turning the Studios into the thrill-seekers’ Disney park, and Sunset Boulevard into the worst bottleneck on property during normal operating hours.

Roller coasters became such a guest draw that in 1996, the Magic Kingdom added a kid-friendly coaster to their new(-ish) land, Mickey’s Toontown Fair, known today as The Great Goofini’s Barnstormer (originally The Barnstormer at Goofy’s Wiseacre Farm). Disney’s California Adventure opened in 2001 with another launching, looping coaster and a rock and roll soundtrack originally known as California Screamin’ (now The IncrediCoaster), and the Studios’ Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster was practically duplicated in the abysmally performing Walt Disney Studios Paris. Additionally, in 2005, Tokyo DisneySea got a near carbon copy of Indiana Jones et le Temple du Péril, sans IP, for their park.

No, wait… That’s Indiana Jones et le Temple du Péril at Disneyland Paris

My mistake — image source: Daily Coaster

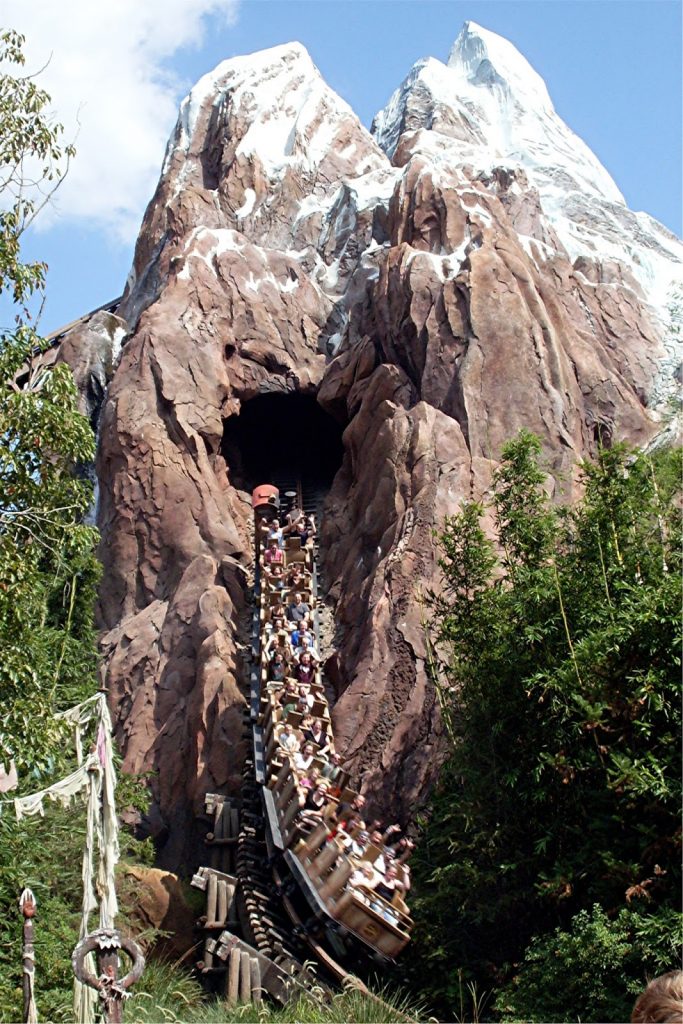

When Disney’s Animal Kingdom was struggling in the early-to-mid-aughts, they added two off-the-shelf carnival rides to the Dinoland USA area, one of which was a “mad mouse” coaster to which was added a teacup ride vehicle, spawning the name Primeval Whirl. When the proposed Beastly Kingdom, which was to feature dragon and unicorn themed coasters, was off the table for reasons we won’t go into here, Disney Imagineering poured $100 million into researching and developing a new coaster featuring a different kind of mythical beast, the Himalayan yeti.

Expedition Everest: Legend of the Forbidden Mountain was groundbreaking in several ways. It was Disney’s biggest coaster to-date, with an 80-foot drop (or 112 feet if you include the drop that leads into the big one). It was the first coaster to travel both forwards and backwards on separate paths of the same track (thanks to a pair of rotating switch-tracks), and it featured the largest and most technologically advanced Audio-Animatronic for the time (it’s still the biggest, despite spending most of the last 15 years being more “audio” and “tronic” than “anima”).

In 2007, Hong Kong Disneyland received another copy of Anaheim’s Space Mountain, and then in the past 10 years, Disney Parks around the world received the following:

- 2012, HKDL: Big Grizzly Mountain Runaway Mine Cars — a hybrid of Big Thunder aesthetics and Everest trills

- 2014, WDW-MK: Seven Dwarfs Mine Train — a hybrid coaster-dark ride with rocking carts

- 2016, SDL: TRON Lightcycle Power Run — a launching coaster with inversions and a motorcycle-style seating

- 2018, WDW-DHS: Slinky Dog Dash — a launching coaster with rocking carts

…and, announced with an expected opening in 2021, Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind in Epcot and a duplicate of Shanghai’s TRON Lightcycle coaster.

image source: Blog Mickey

Whew!

That’s a total of 22 Disney coasters since 1959 (including duplicates, but not including rethemes of existing attractions). Six of those coasters have been built in the past ten years (including the two that have had their tracks built but are yet to open), and more than two-thirds of them have been since 1990. Now, when you consider how many more parks have been built since then, that may not seem out of the ordinary. But when you compare the number of coasters built to the number of new rides built, particularly post-opening, that proportion becomes more significant.

What’s wrong with that?

Roller coasters are a popular ride type in any amusement park. Many parks are built around being only or mostly coasters. Even prior to the ’90s, Disney parks were unusual in that there were few, if any, coasters — and the ones that were there were tame by comparison.

Let’s start by examining why Disney parks used to lack coasters…

They’re scary.

image source: Tips from the Disney Diva

Maybe not to adults like myself and our followers, but to older adults, young children, and less thrill-seeking park-goers, roller coasters can be terrifying — traumatic, in some cases. A lot of people don’t like the sensation of careening out of control, sudden drops, and G-forces. Walt wanted his park to appeal to all audiences, young and old, so he and his WED Enterprises team tended to favor tamer attractions. Although he personally greenlit the Matterhorn and what would become Space Mountain, these were anomalies. In the “After-Disney” era of the ’70s and early ’80s, management was trying to appeal to more teenagers — while also fending off competition from other, more convenient and exciting amusement parks — so Marc Davis’ runaway train coaster from his Western River Expedition was spun off into Tony Baxter’s Big Thunder Mountain Railroad on both coasts.

When Michael Eisner stepped in as CEO, thrill rides became more prominent, but not roller coasters. Eisner wanted more unique, more immersive experiences, not necessarily bigger and faster. Of all the E-ticket attractions from the first “Disney Decade” (approximately 1985-1994), only one was a roller coaster (I’m not counting Indy).

So what changed?

The financial crisis that was Euro Disneyland resulted in a lot of purse-string tightening. The financial crisis that followed the 2001 terrorist attacks tightened them even more. This led to over a decade of minimal expansion and cheap attractions.

You can actually quantify how cheap the attractions got, not in cash, but in Audio-Animatronics. These animated figures, a staple of the Disney Parks, the pinnacle of Imagineering for nearly 30 years, the definitive difference between Disney and other amusement parks, all but disappeared in the ’90s, and haven’t really returned to the degree they were once used (at least not outside of Japan).

Oh, sure, there were the big ones (literally, in the case of DINOSAUR, neé Countdown to Extinction). There was, Ellen, Hopper, a couple of Buzz Lightyears, Stitch, half of Barbossa and 2¼ Jack Sparrows (per coast), a couple of presidents, and probably a few more I’m forgetting about; but compared to the literally hundreds introduced in the ’80s, as well the decade prior, these were meager numbers to say the least.

The correlation between more roller coasters and fewer animatronics is intrinsically linked. Likewise is the overall reduction in ride-through time. When EPCOT Center opened, every attraction ran for at least 10 minutes, usually 15-20. The Great Movie Ride — arguably Disney’s last A-A populated traditional dark ride — ran even longer than that! Disneyland Paris’ Pirates of the Caribbean was and remains the longest version of the attraction… and the park’s initial failure meant it will probably hold that record indefinitely.

The mid-’90s and into the early-’00s saw an influx of shorter, faster attractions with fewer moving parts; longer, more immersive, and elaborate queues; and more exits into gift shops. Even the non-coaster attractions followed this trend. More recently, projections have replaced what would have been three-dimensional sets, animatronic figures, or mechanically animated features pre-1992.

Essentially, the thought process of the time was, if guests are on a ride, they’re not spending money. So we need to get them on the ride, give’m a quick, memorable, and cheap experience, and get them out to the gift shop or concession stand as soon as possible.

“Fewer moving parts”…?

This is the key to the influx of coasters. Just as Audio-Animatronics have lots of intricate mechanisms that have to work perfectly all the time, so do ride vehicles: cars, Omnimovers, flight simulators, Enhanced Motion Vehicles, and even flumes require some form of mechanical locomotion (water jets in the case of flume rides) that need to work constantly, be maintained regularly, and repaired frequently.

Put simply, in addition to the initial cost of research, development, and construction, most of these types of attractions require routine and emergency maintenance to keep the moving parts moving safely and efficiently. Have you ever been evac’d from a Disney ride due to a breakdown? It’s almost always a mechanically demanding attraction like The Haunted Mansion, Carousel of Progress, or Spaceship Earth.

image source: WDW News Today

Coasters don’t have this problem. Coasters have only two or three types of mechanically moving parts:

- The lift: a constant and steadily moving chain with strategically placed hooking points

- The brake zones: pneumatic pumps, only activated in case of emergency, or to stop a train in the unload zone

- A set of small wheels to move the trains out of the load zone and into the first gravity assist.

These account for the smallest portions of the overall ride. The rest is gravity and physics. As long as the safety features are intact, there really isn’t anything to do except turn the ride on and let it go — and since you’re usually moving around at speeds between 30 and 60 miles per hour, there’s not much time or opportunity to look at anything, so decorative and story elements are usually sparse, if not nonexistent.

In other words, Disney could fill their parks with E-ticket thrill rides by designing the track using any number of pre-existing programs, decorating around it, contracting Vekoma or somebody to build it, and then just set it and forget it. Coasters are always pushing large numbers of people through, and they’re on and off within a couple of minutes, ready to buy a T-shirt or pin.

As opposed to something like Spaceship Earth, where there’s a constantly running motor every few cars, dozens of animated figures, synchronized audio, interactive screens, and the whole thing moves at a leisurely pace at which any failure is noticeable.

From a financial perspective, this sounds good — on paper. You can spend a hundred million dollars building an attraction, and a million a year to maintain it, or you can spend a hundred million to build it, but only $50,000 a year to maintain it. (Obviously, I’m making numbers up here, but you get the idea.)

In practice, though, what you end up with is a bunch of loosely themed roller coasters, and not much that’s uniquely Disney. I’m sure I’ve said this before, but I can go to Six Flags and ride a roller coaster. I go to Disney World to ride a monorail, a sternwheeler, a steam-powered train, and a solid hydrogen powered rocket to Mars. I go to Disney World to see pirates, and ghosts, and talking snowmen, and Johannes Gutenberg (that one’s just me? Okay).

I get the appeal of roller coasters. Some of my favorite attractions at any theme park have been roller coasters, like Rock ‘n’ Roller Coaster and Expedition Everest, and I’ll never pass up a ride on Space Mountain. Not only Disney, either. Revenge of the Mummy at Universal Studios and SheiKra at Busch Gardens Tampa are also favorites. A good roller coaster can be a memorable and fun experience, and Disney does some of the best.

But Disney is the best at a lot of things, and it’s a shame to see them focus so much on doing what everyone else does. This is why I’ve been happy to see attractions like Journey of the Little Mermaid, Rise of the Resistance, and Runaway Railway, modern Disney versions of classic dark rides; or Smuggler’s Run, an immersive and interactive flight simulator; or the upcoming Ratatouille ride or Spaceship Earth refurbishment (if it happens). They’re something that pretty much only Disney does.

I’m not saying I’m not excited for the Guardians of the Galaxy coaster, but why did it have to be a coaster? They had one of the largest show buildings on property to start with. They could have used it, maybe expanded it, and built an awesome dark ride in there with a full Audio-Animatronic cast of Star-Lord, Groot, Rocket, et al. It could’ve been a 5-15 minute immersive experience. Instead, we’re getting a 2-3 minute ride with projections and no dimensional sets that somehow takes up four times the space in a show building that is visible from the parking lot and inside the park.

image source: Undercover Tourist

Disney needs a delicate balance. For every big, thrilling roller coaster they install, they should be building slow, unique, dark rides and Audio-Animatronic shows to complement it. I look at attractions like Tokyo’s Sindbad’s Storybook Voyages, Hong Kong’s Mystic Manor, and Shanghai’s Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for the Sunken Treasure, and I get jealous. I watch how much my kids love The Enchanted Tiki Room, Country Bear Jamboree, and Carousel of Progress, and it fills me with joy and nostalgia. When I think of characteristically Disney attractions, these are what I think of. Instead, we seem to just get IP-themed coaster after IP-themed coaster after IP-themed coaster.

The late Iger years were not kind to original and adventurous ideas like the early Eisner years were. The Chapek years have only just begun, so time will tell. Sometimes it seems like creativity has been sucked out of the Disney Company. But we’ve seen all this before. These things are cyclical. Even during Walt’s time, there were creative slumps.

The popularity of Asia’s recent dark rides gives me hope that the American parks will see a return to these someday.

As long as they wait until after the TRON Lightcycles open… 😏

image source: Disney Parks Blog